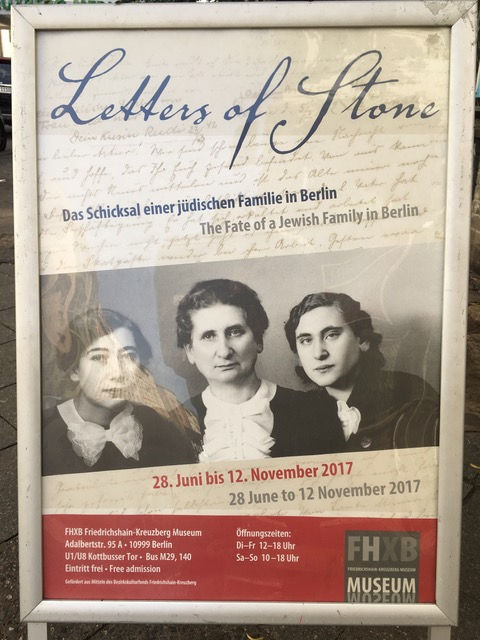

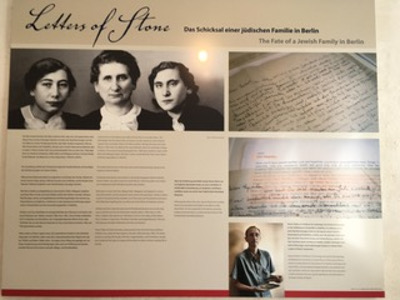

Letters of Stone: An exhibition - the fate of a Jewish family in Berlin

Steven Robins’ long-term project of tracing his family’s past from South Africa to Berlin and back has recently taken a productive new turn with the opening of an extraordinary exhibition at the Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain Museum in Berlin.

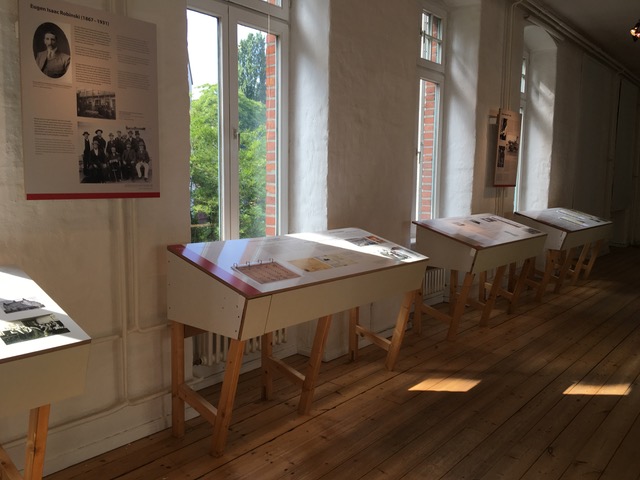

The exhibition, conceived by Stellenbosch University Anthropologist Robins and the museum, and curated by Matthias Rosenthal, is built around the more than one hundred letters that were sent, to the family’s two sons who succeeded to emigrate to South Africa and Northern Rhodesia (today’s Zambia) respectively. The letters were sent mostly by their mother and sister in Berlin, between 1936 when Herbert Robinski, Steven’s father arrived in South Africa and 1942 when the members of the family who had remained trapped in Berlin were deported to Riga and Auschwitz. These extraordinary original papers are contextualised with a documentation of the Robinskis’ earlier family history and a timeline that highlights the increasing suffocation of Jewish life in Germany over the course of the 1930s and early 1940s.

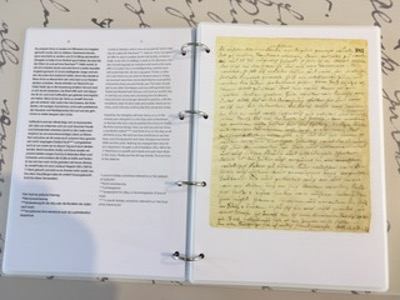

The letters tell a haunting story of the family’s futile efforts to get more of their members out of Nazi Germany; they are chilling where the parents consider which of their adult children may stand the best chance to be accepted into any safe country worldwide. These ponderings sound at times painfully harsh, even merciless. Reading the letters in the museum’s airy third floor exhibition space on a sunny Berlin summer Sunday afternoon, I had more than one chill running down my spine. The reader’s wallets set out on the table in the centre of the exhibition space drew me in, with quite extraordinary potency. The letters, a few typed, but mostly written in old-fashioned gothic German script, are carefully reproduced in facsimile and transcribed in both German and English.

The visitor learns about the story of an extended family dispersed to all corners of the globe in their efforts of escaping the tightening noose of atrocious Nazi anti-semitism. They also give an exceptional glimpse into the everyday life of a very ordinary German Jewish family in the Berlin districts of Kreuzberg and Mitte. The mother writes about little celebrations of birthdays, and Jewish and other holidays. Usually these modest events centrally involve in typically German fashion coffee-and-cake; or Mrs Robinski tells her far-away sons about the father’s social card games with his friends (‘skat’).

Unlike much of what has been documented about Jewish life in pre-holocaust Berlin by the intellectual progenies of the city’s bourgeoisie (think the writings of Walter Benjamin or Franz Hessel!), the Robinskis were part of the city’s working-class; at most some of their number harboured modest lower middle-class aspirations. This is another dimension that makes this exhibition, and Steven Robins’ entire project unique and quite remarkable. Cecilie Robinski’s letters are exceptionally touching where they make even the extraordinary horrors of slave labour sound ordinary, which her elderly husband and adult son and daughters, who had not been able to escape, were forced to do in the early 1940s. She describes them as “a little work” and reports on the (minimal) wages they were paid in a tone that seems almost content. Certainly, she tried to shield her émigré sons from the associated worries; she may have even tried to protect her own perceptions and emotions from the worst anticipations. No reader of the letters, not even her grandson, the researcher and writer Steven, will ever be able to know. Nevertheless, these letters are extraordinary in all their ordinarily-ness.

The exhibition’s scope is broader than what might be suggested by the focus on the haunting family letters. It even goes beyond the contextualisation of the Robinski family’s fate in German Nazi history. Photographs and carefully selected documents also demonstrate the connections between German and Southern African racial science and racism, with a special focus on the career of Eugen Fischer, from his early research in then German South West Africa (today’s Namibia), to his prominent role as an academic pillar of the Nazi politics.

And then, stirring a particularly strong sense, the exhibition carefully documents the mounting administrative restrictions, that South Africa, like most other countries worldwide, adopted in 1936 and 1937 to prevent the acceptance of German Jewish refugees into the country. This connects the fate of the Robinski family to that of the thousands upon thousands who flee war, persecution and impossible conditions of poverty and hunger in their countries today; like thousands upon thousands of German and Austrian Jews in the 1930s they cannot find asylum and are stranded due to anti-migration policies.

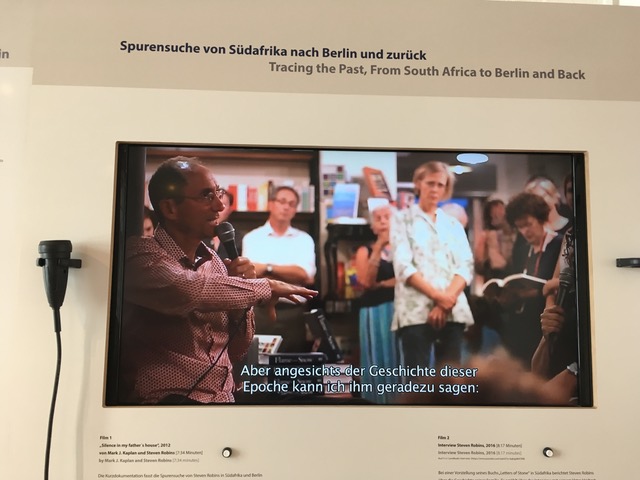

The exhibition succeeds substantially and aesthetically with the combination of the letters, photographs, and explanatory texts in just the right measure. Two brief film extracts complement these. In one we see Steven Robins speaking about the process of tracing his family’s fate from South Africa to Berlin and back; the other clip presents a promotional trailer of the feature film about the fate of the Robinski family, that Steven Robins and the film maker Mark Kaplan are in process of making. This is a haunting story, it is also testimony to deep humanity under trying circumstances.

See my review of Steven Robins, Letters of Stone (2016) available here.