German Colonialism, Genocide, and Memory: Politics and an Exhibition

When former German Foreign Minister Joseph ‘Joschka’ Fischer visited the Namibian capital Windhoek in October 2003 he went on record to say that there would be no apology that might give grounds for reparations for the first genocide of the 20th century, which was committed by German colonial troops in Namibia in 1904-1908.

Only in 2015, official Germany finally acknowledged that the demise of eighty per cent of the Herero and fifty per cent of the Nama of central and southern Namibia indeed constituted genocide when the speaker of the German parliament, Norbert Lammert, penned an article in the influential weekly Die Zeit. Lammert acknowledged that the war crimes committed by the colonial command in Namibia were not merely an unfortunate series of events but that the German command had intentionally aimed at annihilating the local population groups that had risen up against colonial conquest and dispossession. This acknowledgment set a process into motion; now official Namibian and German envoys are talking about the way ahead; the programme involves three steps: acknowledgment, apology, reparations. These negotiations are complicated and contested. Thus far, the envisaged formal apology is still due. On the German side, voices have already ruled out reparations. In Namibia, members of the affected communities have claimed that they be part of a more inclusive process. In October 2016, an international civil society congress brought together Herero and Nama from around the world with German solidarity activists in Berlin to discuss the way forward.

Coinciding with this activist event, a major exhibition, entitled “German Colonialism: Fragments Past and Present”, opened in the German Historical Museum (Deutsches Historisches Museum/ DHM) in Berlin. This exhibition addresses German colonialism, a topic which has been muted until now for several reasons, including the early demise of formal Germany’s colonialism after World War 1, which meant that the period of nationalist struggles to end colonialism in the late 1940s and 1950s largely eluded the German public. Importantly, the exhibition narrative in the museum and the accompanying fat catalogue claims, it was the horrors associated with the 1940s Nazi atrocities in Eastern Europe that dominated German memory in research and public discourse over the past few decades.

Starting from the history of German colonial conquest within a global context, the exhibition presents, through images and texts and a large number of objects, mostly drawn from the museum’s collections, colonial fantasies, colonial rule, warfare and violence as much as the everyday of life, the complex negotiations, and the boundary-making between colonizers and the colonized in the former German colonies in Africa, Asia and the Pacific. The exhibition does not conclude with the formal end of German colonialism after Word War I; an extensive presentation depicts colonial revisionism between 1919 and 1945, while also showcasing examples of the numerically insignificant but radical anticolonial resistance in the Weimar Republic, most prominently featured in the popular ‘Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung’ (Workers’ Illustrated Review). This important section is appropriately titled ‘Colonialism without Colonies’ and demonstrates that the colonial revisionist rhetoric directed at Africa in the end evolved into the Nazis’ violent attempts of colonizing the European East during World War 2. Of course, this is where the genocides of the 1940s were committed, including the holocaust of the European Jews, the mass murders of the Sinti and Roma, and other ‘undesirables’. In true colonial style the East European Slavic population was subjected to serf status. Through this wide sweep, the exhibition connects the violent colonial relationship, and its consequences for a racist ideology, which prepared the ground for the colonial as much as the Nazi genocides.

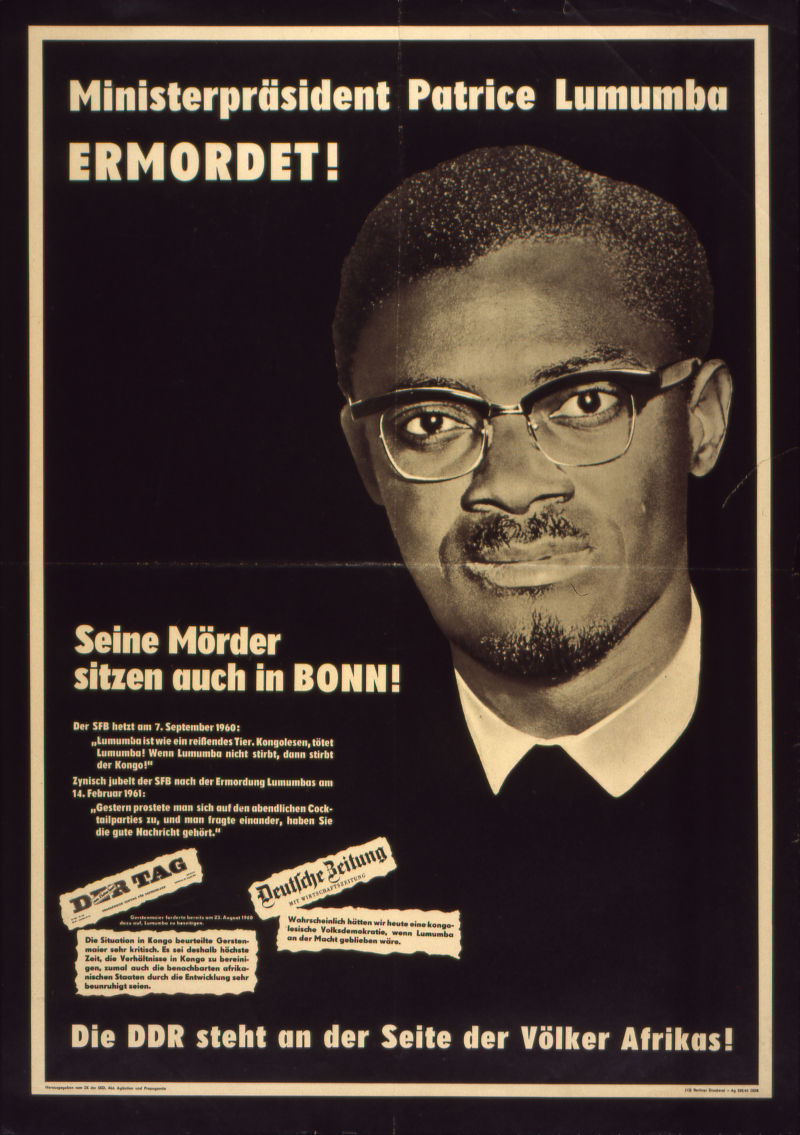

In the following section, the curators showcase the different trajectories of West and East German decolonisation and memory discourses during the Cold War era until German unification in 1990. They display centrally, for the West, the broken statue of infamous colonial icon Herrmann von Wissmann, which was toppled by radical students in Hamburg in 1968. Next to it, visitors can watch a tv programme in which the protesters discuss their action. For the East, an official poster calls to a rally on the occasion of the murder of Patrice Lumumba, which includes the line that the West German government had also been party to Lumumba’s assassination. Hence, the exhibition points out that while in the West anticolonial initiatives were operating in opposition to the State, in the East they were driven by the ‘communist’ regime, although in both German states official and everyday racism remained rampant. In the final section taking the questions of colonialism and racism into the present, the exhibition presents contemporary anticolonial and antiracist initiatives active today.

What to make of this exhibition? It has generated much controversy, coming from different sides. Some decolonisation activists from Berlin, and Namibian communities objected to the exhibition, which, they say, excluded those directly affected. During the official exhibition opening, participants of the Nama and Herero civil society congress staged a protest outside the museum. On the other hand, numerous visitors complained – recorded in the visitors book and on the DHM facebook page - that the exhibition was biased and presented German colonialism in an allegedly ‘one-sided’ and ‘prejudiced’ negative light, which was supposedly ‘unfair’ towards the colonial administration and Schutztruppe colonial army,

Notwithstanding the understandable objections regarding the inclusion (or exclusion) of those from former German colonies, my personal take is, this is an overdue endeavour and quite a superb exhibition. I like the interplay between presentations of the truly horrific violence of colonial rule, and the everyday-ness of it. I also like the fact that colonialism is presented as intertwined with processes of globalisation from the start. The exhibition is not perfect, it doesn’t even claim to be so. It is self-proclaimed fragmented, no doubt, but, and I think this is really crucial to representing this history today, much is focused on the aftermath, and particularly the challenges Germany – and the rest of the European former colonial powers – face in the early 21st century. This is obvious since the early 20th century genocide of the Namibian Herero and Nama is a central theme, in the exhibition’s historical narrative as much as in the current debate in official and civil and political society Germany. Another prominent topic of the exhibition is twenty-first century racism, and so are the traces of the colonial past, in street names, and not the least in the collections of museums and the still hotly debated new Humboldt Forum project across the street from the museum, where the reconstructed Prussian city palace is nearing completion. Berlin’s ethnological museums will be relocated to the reconstructed palace in the centre of the imperial city. The new site will focus on exhibiting the exotic, or so critics say. Critics of the Humboldt Forum undoubtedly have a point.

The colonialism exhibition currently on show in the German Historical Museum however is, I found, remarkably honest about its own shortcomings as a museological endeavour, which is both provisional and profoundly political.